Numbers show regressive impact of Russian ban in skating. Is the decline good or bad?

/Alexandra Trusova started a jump revolution in women’s skating that has stalled in her absence and that of her Russian compatriots.

So here we are, hard upon a second straight figure skating Grand Prix Final without Russian entrants as justifiable punishment for their country’s unprovoked invasion of Ukraine, still waiting on a decision in the soap operatic Kamila Valieva doping case almost two years after the Russian phenom tested positive six weeks before the 2022 Winter Olympics.

The Valieva decision, which has delayed awarding the 2022 team event medals, is expected by mid-February. That presumably is mid-February 2024, but who knows? Anyway, it can go on the back burner for today’s discussion, which is about the state of the sport without the beleaguered Valieva and her compatriots as the Grand Prix Final begins Thursday in Beijing.

There is no doubt that the absence of the Russian women, who had utterly dominated the sport since 2014, has had a dramatic effect on jumping.

During the last season in which Russians were allowed to compete (as Russians) internationally, 2021-22, there were 13 quadruple jump attempts in the six senior Grand Prix “regular season” events: eight quad toes, two salchows, two flips and a lutz.

Six quads were in combination; 12 received positive grades of execution; all were by four different Russians.

In the last TWO seasons, without Russians, there have been just four solo quad attempts in 12 Grand Prix events – two each season, only one of the four with positive GOE, all quad toes, all by Japan’s Rion Sumiyoshi.

So the jump revolution in women’s singles, which began in 2018 with a quad by Alexandra Trusova, then 13, seems to have been beaten back – at least temporarily.

Is this good? Has it reduced the pressure on younger skaters to practice jumps that put both mental and physical strain on barely pubescent and prepubescent girls, some driven by martinet coaches, some driven by competitive desire, some driven by both?

Available statistical evidence culled from the invaluable skatingscores.com suggests that has not happened in Russia.

Over the course of the 21/22 season, in international and significant national events compiled by skatingscores, junior women attempted 69 quads – 56 by 12 Russians, three by Americans (Mia Kalin and Isabeau Levito), one by a Japanese.

Last season, with Russians able to compete just domestically, junior women made 53 quad attempts, 40 of them by nine different Russians, seven by U.S. skater Mia Kalin, six by Japan’s Mao Shimada.

At what is essentially the mid-point of this season, juniors have made 40 quad attempts, 29 by 12 different Russians, six by Kalin, five by Shimada.

Kalin is the only non-Russian to have a quad with a positive GOE. (Just one of her six.) Of the 29 Russian quads, 12 were positive.

What this likely means is as soon as Russia is reinstated, even with the higher age minimum (17) for senior events, it will almost certainly have plenty of young women ready to jump to the top, as Valieva, the 2022 Olympic champion Anna Shcherbakova and the 2022 Olympic silver medalist Trusova did with quads from 2018 through the last Olympics.

That will end the “interregnum” in which women with less demanding jumps have been able to make podiums (and even win the last two world titles) without even a triple lutz-triple toe combination, let alone quads (or triple axels).

To some, that is a refreshing change, helping level a playing field (especially for older skaters) that had titled dramatically toward athleticism and away from artistry and performance.

To others, it is a step backward in a sports world where the Olympic motto of “Faster, Higher, Stronger” generally applies.

Are we seeing regression to the mean? Or just regression?

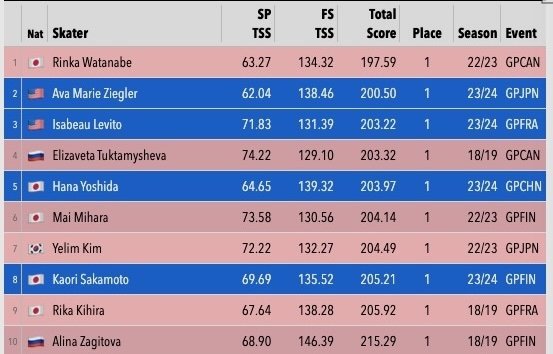

Ten lowest women’s winning scores in Grand Prix events beginning in 2018-19. Highlighted in blue are scores from this season. (Table by skatingscores.com)

By the measure of winning scores in women’s singles at Grand Prix events this season, it looks like regression.

Starting with the 2018-2019 season, when significant scoring changes went into effect, only one of 30* Grand Prix winning scores (Rinka Watanabe of Japan’s 197.59 at 2022 Skate Canada ), has been lower than those this season of U.S. skaters Ava Marie Ziegler (200.50, NHK Trophy) and Levito (203.22, France.)

The fifth and eighth lowest winning scores over the last five seasons also have come this fall.

(*This does not count scores from the 2020 Grand Prix season, when the Covid pandemic made the events domestic competitions.)

The same is true for the Grand Prix in pairs, the other discipline in which the absence of Russians has the greatest impact.

The lowest, fourth lowest and fifth lowest winning pairs scores beginning with 2018-19 all have come this season (as have the 10th and 11th lowest.)

The lower numbers clearly indicate a drop in the overall quality of singles and pairs. Only a Pollyanna would argue otherwise.

Whether this backsliding will continue until the Russians are allowed to return is yet to be seen.

Meanwhile, men’s skating – the discipline in which Russia has had by far the least recent success – is as good and as technically advanced as ever. Japan’s Yuma Kagiyama and Shoma Uno, France’s Adam Siao Him Na and America’s Ilia Malinin could provide drama and fireworks in the Grand Prix Final.

In ice dance, the evergreen U.S. team of Madison Chock, 31, and Evan Bates, 34, reigning world champions, can be celebrated as soon as they step on the Beijing ice for the rhythm dance. It will be their seventh appearance in a Grand Prix Final, matching the record for ice dancers shared by Marina Anissina - Gwendal Peizerat of France and Marie-France Dubreuil – Patrick Lauzon of Canada.

Chock and Bates first competed in the Grand Prix Final in 2014, when they finished second for the first of four times. Based on top scores this season, in which their best ranks behind those of Canadian, British and Italian teams, Chock and Bates would need a big jump – mathematically, at least – to win the title.