Smith and Carlos to represent for Team USA. Right on.

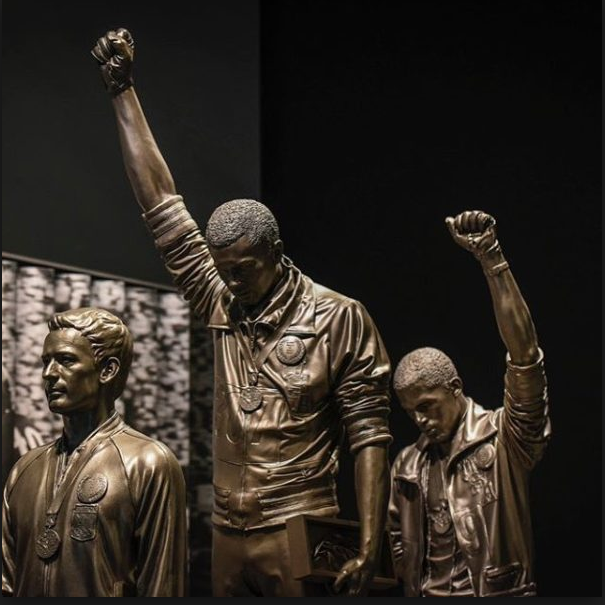

/The sculpture at the new National Museum of African American History and Culture portraying the now iconic 1968 Olympic podium protest by Tommie Smith (center) and John Carlos (right).

It was going to be just a gesture of reconciliation, a long overdue welcome back for sprinters Tommie Smith and John Carlos, an invitation for them to be part of the Olympic family in the United States again after nearly 50 years as institutional outcasts.

Now, thanks to an accident of timing and the good intentions of the U.S. Olympic Committee leadership, it can be so much more.

There is a backstory here, and I will talk about it later. But, right up front, it should be said that the USOC’s asking the two 1968 Mexico City medalists to be U.S. Olympic ambassadors and to accompany members of the 2016 Olympic and Paralympic teams on their White House visit Thursday is an important statement in these troubled times for our nation.

“The conversation they started in 1968 is still relevant today. They are still relevant today,” USOC spokesman Patrick Sandusky said.

Smith and Carlos spoke in 1968 by standing shoeless on the awards podium, bowing their heads and making a raised-fist, black-gloved salute during the playing of the National Anthem in the medal ceremony for the 200 meters, which Smith won with Carlos third.

It was a peaceful protest in favor of human rights worldwide, a peaceful show of solidarity with their black brothers and sisters at a time when many African-American leaders had called for a black athlete boycott of the Olympics, a time when racial tension in the United States was overwhelming in the aftermath of the 1968 assassinations of Dr. Martin Luther King and Bobby Kennedy.

The protest made Smith and Carlos pariahs in an Olympic family led by Avery Brundage, the autocratic, anti-Semitic, misogynistic, morally tone deaf Chicagoan who was then president of the lily-white International Olympic Committee (one black among some six dozen IOC members, all men, in 1968).

At Brundage’s urging, Smith and Carlos were unceremoniously booted from the Olympic Village and sent home, where they faced death threats and less sinister opprobrium in much of their deeply divided country. (Silver medalist Peter Norman, a white Australian who joined Smith and Carlos in wearing an Olympic Project for Human Rights badge, also would be scorned in his homeland.)

It also made the sprinters important figures in the ongoing Civil Rights Movement. At the new National Museum of African American History & Culture in Washington, a sculpture of their podium protest stands at the entrance to the sports gallery.

And now they are coming to Washington, at a moment when their protest has been echoed for nearly a month by athletes in several sports, including NFL and college football, the WNBA and women’s soccer. The Chiefs’ Marcus Peters recalled them by raising a fist. Those athletes all want to start a new conversation about race relations after a relentless wave of fatal shootings of African-Americans by police.

So we have Smith and Carlos representing Team USA. It is symbolically powerful. And it seemed so unlikely.

+ + + + +

The United States Olympic Committee is, ipso facto, the country’s most overtly patriotic sports organization. (After all, its athletes wear “USA” on their uniforms.) It is also an organization whose past leadership had very conservative leanings – after being chartered by Congress in 1978, the USOC’s first two executive directors were a retired Army colonel and a retired Air Force three-star general – and has its headquarters in a very conservative place, Colorado Springs.

Dating to Jesse Owens in 1936, many black athletes have been stars on U.S. Olympic teams. Yet the USOC and the sports federations it oversees, like nearly every company, university and non-profit in this country, have struggled to get near the goals for inclusion and diversity they have set, as USOC chief executive Scott Blackmun noted in a speech to last week’s Olympic Assembly in Colorado Springs.

Blackmun, whom associates describe as a true political independent, had never met Smith or Carlos until hurdles legend and two-time Olympic champion Edwin Moses introduced them at a reunion of some 300 Olympians and Paralympians in Las Vegas last March. It was the first such reunion in eight years and the first in Blackmun’s tenure as CEO.

When the athletes were introduced after the dinner, among the loudest cheers were those for Smith and Carlos, never pariahs among their peers. That prompted Blackmun to begin thinking of how to bring them formally back into the fold.

Even if some within the U.S. Olympic movement may still disagree with the action Smith and Carlos took in Mexico City, almost no one thinks they should have been excommunicated since. Before the Rio Olympics began in early August, Blackmun brought up at a USOC board of directors meeting the idea of naming them ambassadors.

Tommie Smith (left) and John Carlos after receiving the Arthur Ashe Award for Courage at the 2008 ESPY Awards.

When the board agreed, the feeling was the best place for an announcement would be the annual U.S. Olympic Assembly, attended by leaders of all this country’s Olympic-related sports organizations.

Reaching out to Smith and Carlos was to be mainly a statement about the USOC’s commitment to having a better record on putting women and minorities in both its management and staff and those of the National Governing Bodies.

“I think Tommie and John have played an important and positive role in the evolution of our attitudes about diversity and inclusion, not only in the United States but around the world,” Blackmun would tell the Assembly last Friday. “And in recognition of that, we have asked Tommie and John to become ambassadors for us as we fight for greater inclusion within the U.S. Olympic movement, and they will be coming to Washington, D.C., with us next week.”

The rationale still rings true. But the context has changed dramatically since the USOC decided to have a formal rapprochement with the sprinters, now 72 (Smith) and 71 (Carlos). Having them join Team USA in Washington will make them part of the heated debate about the recent athlete protests during the National Anthem, and some of those who vociferously and irrationally criticize Colin Kaepernick and others who have followed his example undoubtedly will make a target of the USOC.

It would have been easy for the USOC to leave this at naming Smith and Carlos ambassadors and not inviting them to Washington. That didn’t happen, hopefully because Blackman and others realize how much courage it took for Smith and Carlos to do what they did in 1968.

Whether in powerful wordless gestures or in words, Smith and Carlos’ message sadly must still be delivered as forcefully now as it was in Mexico City. The USOC will be on the side of our better angels if it is seen as endorsing that message by having Smith and Carlos at the White House.

That is what Tommie Smith and John Carlos represent. They represent the Team USA we should all be on, the one that speaks out against injustice and works to remedy it, the one that defends the flag and the Anthem not with false patriotism but by reminding us how far we have strayed from the values those symbols stand for, the values so eloquently expressed in the second paragraph of the Declaration of Independence.

And where better to represent than Washington?