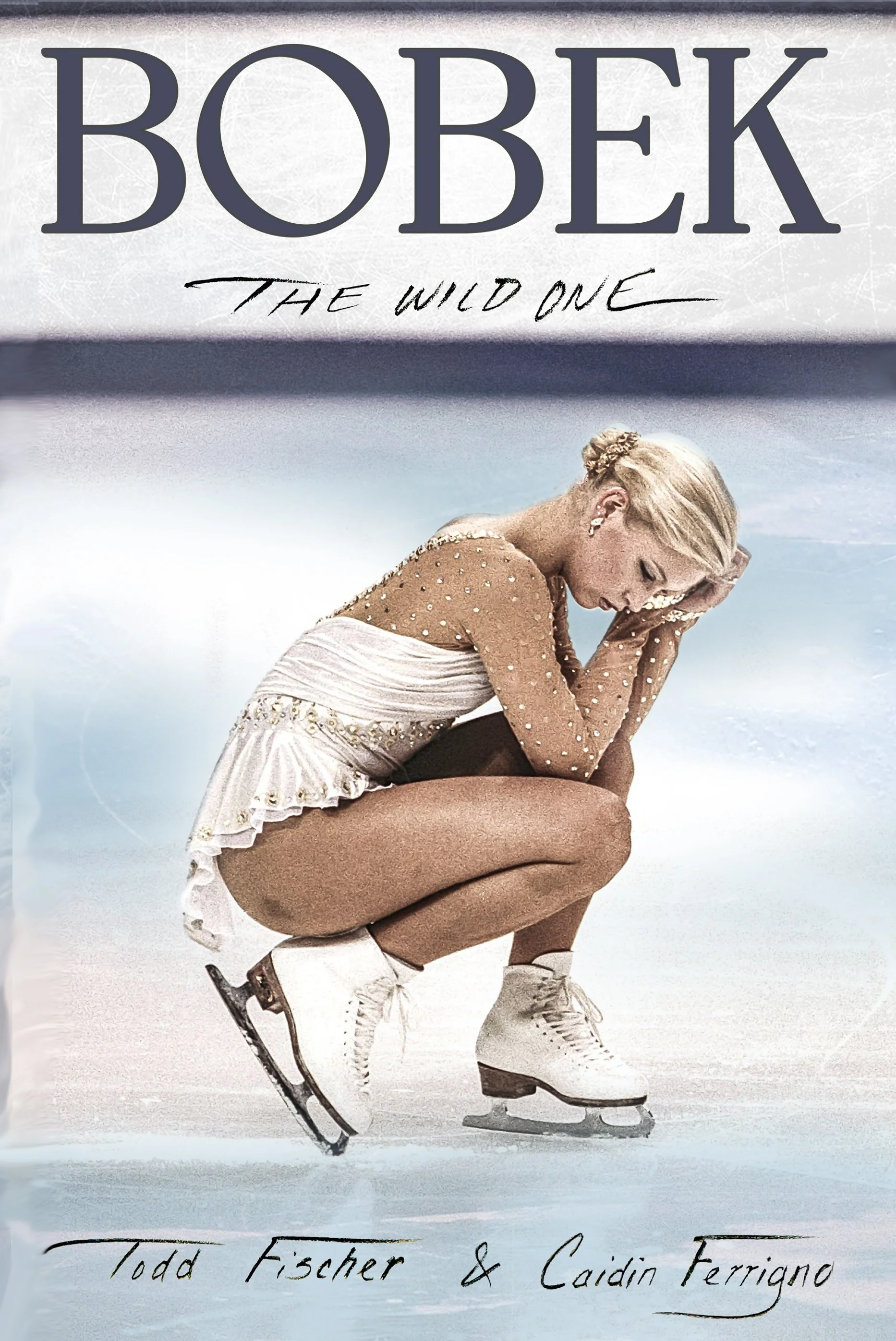

In memoir, skating champion Nicole Bobek confronts her past head-on, frightening details and all

/It's wild how fast life can flip. On minute, you’re center ice with the world at your feet. . .The next you're barefoot in a Florida jail cell shaking so hard you can't even hold the phone steady enough to dial your mom, let alone speak when she answers.

--Nicole Bobek in her new memoir, “Bobek: The Wild One”

I texted Nicole Bobek last month to let her know I had received the review copy of her book. She replied, “You might wanna put on your seatbelt for this one.”

Indeed. As the excerpt quoted above (and those to follow) illustrates, the figure skating champion’s life (lives?) has been a bumpy ride, with more than one crash landing.

I knew the rudiments of her story, from my having written some 200 Chicago Tribune stories in which Bobek’s name was mentioned (she was the sole subject of dozens) from 1990 to 2012. In one of those stories, published in 2010, Bobek allowed me to be the first to outline her descent into the hell of crystal meth addiction.

It was a hell she finally escaped only after pleading guilty to a level two conspiracy of manufacturing/distributing/dispensing the drug and getting five years probation.

Even knowing all that about her, I was overcome with a feeling not unlike air sickness as I read Bobek’s recounting of the gruesome details related to her addiction – the rotting teeth, the abscesses, the 11 days in jail – as well as the other setbacks she has endured in the 16 drug-free years that have followed.

Her broken marriage. Her other failed relationships. Her stints plodding through Scandinavian mud with a picaresque circus troupe. Her teetering on the abyss of insolvency – this for a woman who made an aggregate of nearly $2 million from the Champions on Ice show alone during the 10 seasons she toured with them following her 1995 U.S. title.

She was a charismatic performer who once had had contracts with Danskin and Campbell’s and was pictured in Vogue. By 2024, she says in the book, she was selling prized possessions and eating ramen noodles to stay afloat.

With the exception of a few texts we had exchanged about her Instagram posts, I had no real contact with Bobek, now 48, for the 13 years before we talked last week about the book, which goes on sale Wednesday. Reading it filled me in on what happened to her during the time we were out of touch – and of all the other discomfiting things before then that I had been unaware of.

I still knew her mostly from a competitive skating career that might have been more decorated had she not struggled with injury, indifference, self-doubt and failed attempts to find the person inside the skater.

Nicole Bobek’s mug shot after her 2009 arrest.

“Looking back now, I don’t regret any of it. That fire, that rebellion – it’s what kept me going. They called me the wild child like it was an insult. But honestly, that label never scared me. What scared me was the idea of shrinking myself down to make everyone else comfortable.”

—From “Bobek: The Wild One.”

She had a stunning and natural relationship to music. The most breathtaking spiral I ever have seen. By the end of the 1995 season, at age 17, she was national champion and world bronze medalist, claiming the first with an ugly secret hanging over her and the second after it had been revealed.

She would change coaches 11 times (Or was it 111? ) Her attention deficit disorder and often defiant resistance to what coaches and skating officials wanted only exacerbated her problems.

“Like trying to nail Jell-o to the wall,” JoJo Starbuck told me.

Starbuck, the Hall of Fame pairs skater, had done some choreographic work with Nicole. She also was among those who wrote the judge sentencing Bobek in the hope he would approve the probation rather than the 364 days of jail time the prosecutor asked for in the drug case. Given the skater’s past, Starbuck’s support required a leap of faith that Bobek since has justified.

After all, the drug charges weren’t the first criminal charges she had faced.

In 1995, she got two years probation after a conditional guilty plea to a felony home invasion charge in Michigan. The record of what Bobek insists was a misunderstanding was supposed to remain sealed pending her fulfilling the terms of the probation, but word of it leaked. The charges eventually were dropped.

This was a year after the Kerrigan-Harding imbroglio. The idea that another U.S. women’s champion wasn’t exactly an ice princess proved irresistible to the British tabloid media during the 1995 World Championships in Birmingham, where they nicknamed her “brass knuckles.” Headlined the usually staid (and non-tabloid) Times of London: “Brass Knuckles prospecting for skating’s precious medals.”

"I was just thinking," coach Frank Carroll said to me right after Bobek won the 1995 U.S. title (and before the criminal case became public,) "we've gone from Tonya Harding to Nicole Bobek. Oh, my God!”

A year later, Bobek withdrew from nationals in San Jose after the short program with an ankle injury that had gotten worse because she rejected her then coach’s advice and chose the financial benefits of starring in a Nutcracker on Ice skating tour over the benefits of recovery time before nationals.

It was the beginning of the end of her very brief stay atop a U.S. women’s scene soon to be dominated by Michelle Kwan and Tara Lipinski.

In a sad footnote, that fateful tour not only affected her figure skating career but was also when she met the person who several years later would introduce her to crystal meth.

I left San Jose not as the reigning champion, but as an afterthought. I was 18 years old and felt like a fraud. And the worst part was that I knew it was coming. I'd let it happen. I walked straight into it but still it hurt. It hurt like hell.

--From “Bobek: The Wild One.”

Like many athletes, Bobek struggled with the notion that her entire identity was tied to the sport.

The truth is skating was the one constant in Bobek’s life, the one thing that kept her somewhat tethered to a plan.

She managed bronze medals at the 1997 and 1998 nationals, good enough to make the team for the 1998 Olympics. But she went there bothered by a persistent hip injury and finished a dismal 17th in both the short program and the free skate.

A year later, Bobek retired from Olympic-style competitive skating at age 22.

The path I had been on since I was a little girl was gone. There were no more nationals, no more Olympic dreams, no more trying to prove myself to judges who’d never quite known what to do with me in the first place.

--From “Bobek: The Wild One.”

In 2004, not long after giving Bobek an expensive watch to mark her 10 years on tour, Champions on Ice impresario Tom Collins dropped Bobek from his roster because her performances had become sloppy and erratic. Suddenly, she was entirely unmoored and heading for a world filled with cocaine and meth and clubbing in lower Manhattan, of doing little more than getting high.

Occasionally, she would get a contract to perform in an ice show. Then she would mail in the performance, her pride completely gone.

Drugs and partying had taken everything from me- my focus, my drive, my body, and my soul.

--From “Bobek: The Wild One.”

Nicole Bobek on the lyra - with her skates.

Every so often, she would return to her mother’s home in Florida to dry out. That is where she was in 2009 when police arrived to arrest her on the drug charges in New Jersey, to which she would be extradited and spend 11 days in jail.

She had finally hit rock bottom. Skating had taught her the only thing to do was get up.

That process took the better part of the last 15 years, a period in which she was knocked sideways by her pattern of falling into toxic romantic relationships. One was with a circus acrobat. . . and, well, she ran away to join the circus.

Bobek would go on to train at a circus school in Miami and become a specialist on the lyra, or aerial hoop. To that she added the fillip of flying 40 feet in the air while wearing skates, so she could perform above an ice surface, then glide away after she landed. She did both an aerials performance and a skating performance in the 2015 tour of Nancy Kerrigan’s “Halloween on Ice.”

She married circus performer Pedro Leal in 2017. The marriage ended in divorce seven years later.

Bobek and Leal had a son, Alejandro, in 2020, on their third attempt at IVF. She was 42 at the time.

Nicole Bobek and her son, Alejandro, near their Florida home. (Courtesy Nicole Bobek.)

She and Alejandro live in a rented house in Lake Worth, Fla., not far from Bobek’s mother, Jana, and her husband. Nicole never has known her birth father.

When we spoke via Zoom last week, Bobek said, “Having a child gave me the superpower to write the book.” She had rejected suggestions to do a book in the immediate aftermath of the sex, drugs and rock n’roll chapter of her life.

As she had when I went to see her in 2010, Bobek again took full responsibility for her actions during our recent conversation. And she is determined not to live in the “state of could have, would have should have,” retelling the past as both a cautionary tale for others and a self-affirming statement of the progress she has made. It was also an exercise in acknowledging how lucky she feels still to be alive.

“ I've been through hell, and I'm still here, still existing,” she told me. “I've survived somehow 100% of my worst days, and I've moved forward.”

The abscesses on her body, face and inside her mouth have healed. Hours of sophisticated dental work fixed her teeth.

At some point, she stopped posting on Facebook under a pseudonym and began posting on Facebook under her own name.

Her days now are blissfully routine, revolving around her son. Taking Alejandro to school, to t-ball, occasionally to skate together on the rink where she gives lessons. Bobek also does some virtual lessons.

“I love being a mom,” she said,

Money hasn’t been as significant an issue since the sale this year of the 7-figure waterfront home she purchased at the height of her financial success. She has spent much of this year working on and now promoting the book, which she hopes might lead to someone wanting to tell her story for television or roles in shows.

There's no neat ending here. No bow to tie around the wreckage. I didn't write this to make excuses or to settle scores. I wrote it to tell the truth - my truth. The good, the bad, and the parts I wish I could forget.

-- From “Bobek: The Wild One.”

Nicole Bobek still is writing the ending.